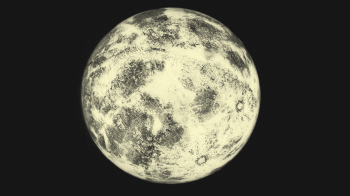

Sometimes beauty reveals itself in the most unexpected places. It could be in a cup of coffee, for example, or in the room of a girl in a yellow dress. It’s in your own mind. Yasmijn Karhof’s short film ‘Play within a play’ begins with a reflection of the moon, although we cannot see what it is reflected in. Strange sounds like the chirping of crickets are audible in the background, and somewhere we hear the rattle of crockery. A train rumbles by; the moon begins to turn and swirl, finally breaking up into shimmering patches of light no less beautiful than the original image. By this point the presumed reality has slipped from our grasp. Is this a lake? A night sky? It is not until the camera zooms out that the moment of disillusion strikes. We see only a table bearing a cup (Arabia, dark blue) of coffee in which an electric light (a simple, bare bulb) is reflected. A dark man in a royal blue shirt picks up a coffee spoon, and you can’t help thinking leave the moon alone! Don’t stir the coffee! Please don’t drink it! The nonexistent moon has clearly found a place in our hearts. It has a vulnerable beauty to which we are now attached. Pleading is in vain: the man stirs and drinks the coffee.

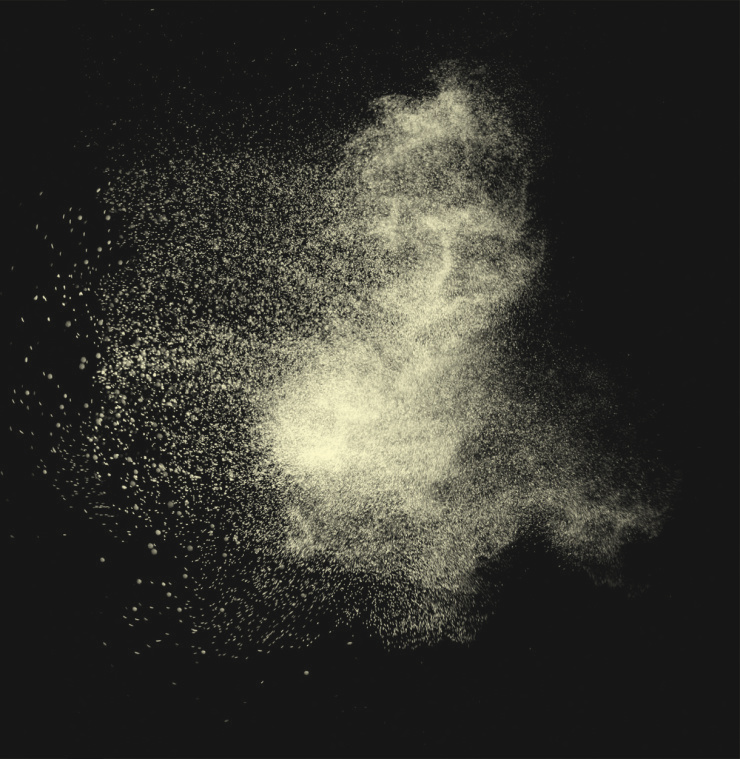

Karhof’s ‘Play within a play’, a triptych, is full of paradoxes like this. Where does reality end and the imagination begin? How vulnerable do you become when you succumb to beauty? Fascinatingly, it is not only the spectator who faces these questions; the characters in the film are unmistakably struggling with them too. The longer and more often you watch the film the clearer it becomes that, for the dark man and for the red-haired woman who appears in parts two and three, reality and imagination are tightly interwoven. The effect is especially striking in the crucial image of part two, when we see the woman for the first time. She is sitting on the (sky blue) floor of a room, clad in a wide-falling, bright yellow dress (the sun!), alongside a small sheepskin rug (a fleecy cloud) and a book that lies open at a photo of a flying seagull. It is a splendid image, literally heavenly, and it is hard to believe that this is not partly due to the woman’s total preoccupation with the almost lava-like shimmering in the bowl of miso soup which she holds. Once again, we are forced to wonder whose perception prevails: is it that of the woman, of the filmmaker or of yourself?

There is no answer to that, but who needs one? The image is too beautiful for that. Beauty is the prominent quality of this film (which could equally have been titled ‘Play within a play Within a Play’). Karhof constantly diverts everyone – the viewer as well as the characters – between varying ideas and feelings, until no one can recall where he or she stands. What is real here? And if it is no longer real, what is it then? It grows increasingly clear as we watch the film that the fluctuating emotions could drive the two protagonists apart, so compelling us to think about the inherent potency of beauty. In this respect, ‘Play within a play’ offers us a powerful hint of the sublime, of the idea that beauty can exert a power so imposing and overwhelming that it eludes the grasp of the human mind. Perhaps that is what really happens with Karhof’s characters. Beauty is, for them, both an intensification of reality and a retreat from it. But can it bring them together despite all? When you have watched ‘Play within a play’, you realize that beauty can destroy as well as unite. That is the true intensity of what you have experienced.

Back to TEXT